When Jim Croce passed away in a plane crash in 1973, he left behind a wife, a son who became an excellent musician in his own right, and five absolutely fantastic albums. Of these five records, three were critically lauded, and one would not be released until three months after Croce’s death.

Nuanced and nostalgic, Jim Croce’s slice-of-life songwriting evokes the every day in a way that few artists before or since have been able to emulate. His songs speak to the common man, telling stories of good-time barroom brawls and gut-wrenching heartache while waxing philosophical on the state of life. These tales and messages are sewn into a lovingly layered acoustic sound that belongs to the soundtracks of cool summer evenings and stretches of highway disappearing into the purple dusk. His last three albums in particular contain some of the greatest folk tunes of the 1970s, an impressive feat considering they were all released in a span of less than two years.

Croce was born on January 10th, 1943, in South Philadelphia. His parents, James and Flora, were second-generation Italian-Americans. Croce was fascinated with music from a young age, learning to play “Lady of Spain” on accordion by the age of five. At age 15, he begged his father for a guitar so that he could write his own tunes. His father eventually acquiesced, pawning his other son’s unused clarinet to purchase a used guitar for the young musician. However, music was not a serious pursuit for Croce until he reached college. Attending Villanova University, Croce became involved with several school music groups. From there, Croce would go on to form several bands, performing at bars and coffeehouses and making a name for himself in the local Philly scene.

“[We played] anything people wanted to hear,” Croce said in an interview reminiscing on his earlier years, “blues, rock…railroad music… anything.”

Croce’s band would go on to be selected for a foreign exchange tour of Yugoslavia, as well as parts of Africa and the Middle East. Croce described the experience fondly later in life: “We just ate what the people ate, lived in the woods, and played our songs. Of course, they don’t speak English over there, but if you mean what you’re singing, people understand.”

Despite a strong local following in Philidelphia, success was slow to come for Croce. Shortly after marrying his wife, Ingrid in 1966, he would go on to release his debut album Facets. Funded with a $500 wedding gift from his parents, Croce pressed 500 copies. His parents gifted him the money for the album to show the young singer-songwriter that he could not support a family as a musician. They hoped that a bad experience would convince Croce to settle down and put the idea of fame behind him. The plan backfired, however, after the album sold out at local gigs and turned a profit of $2500. Croce’s second album, Croce, came in 1969. The only album to feature Ingrid Croce, the duo moved to New York after its release before touring extensively through the East and South. Unfortunately, the LP failed to sell. By late 1969, the couple had quit touring and settled in the small town of Lyndell, Pennsylvania, having become disillusioned with the business side of the music industry of New York. A year later, Ingrid was pregnant with a son, A.J.

With the impending birth of his son, Croce was determined to take one more shot at the music business. In just over a week, he had penned five songs: “Time in a Bottle,” “Operator (That’s Not the Way it Feels),” “New York’s Not My Home,” “Photographs and Memories,” and “You Don’t Mess Around with Jim.” These would form the base for his third album, You Don’t Mess Around With Jim. After being rejected by 40 music labels, ABC Records picked up the album and released it in April of 1972. It quickly shot up to #1 on the Billboard Top 200. It remained on the charts for 93 weeks, and its singles “Operator (That’s Not the Way it Feels)” and “You Don’t Mess Around with Jim” are considered two of Croce’s biggest hits. Croce appeared on national television, performing on The Tonight Show and American Bandstand among others.

The album was also the first to feature the guitar stylings of Croce’s musical partner and friend, Maury Muehleisen. Together, the two musicians created a melodic, acoustic backdrop that combined elements of country, blues, folk, and pop. Croce would pair these melodies with story-like lyricism. An everyman’s poet, Croce’s songs have an immortal relatability to them; he tells vivid stories of heartbreak and freedom, invigorating triumph and devastating loss. In between, he spun little tunes that poked fun at the ridiculousness of it all and kept his catalog from becoming deathly serious.

From the triumph of the underdog in “You Don’t Mess Around with Jim,” to the hollow loss of love and friendship described in “Operator (That’s Not the Way it Feels,) to the brutal reality checks of “Box #10,” Croce wrote songs in cleverly beautiful turns of phrase. Lines like “She’s living in L.A., with my best old ex-friend Ray,” and “I got a pipe upside my head, left me in an alley, took my money and my guitar too,” say so much with so little, and the inflection of Croce’s vocals imparts a sincerity to his music that made the audience feel as though one of them had gotten up to sing the regular Joe’s blues.

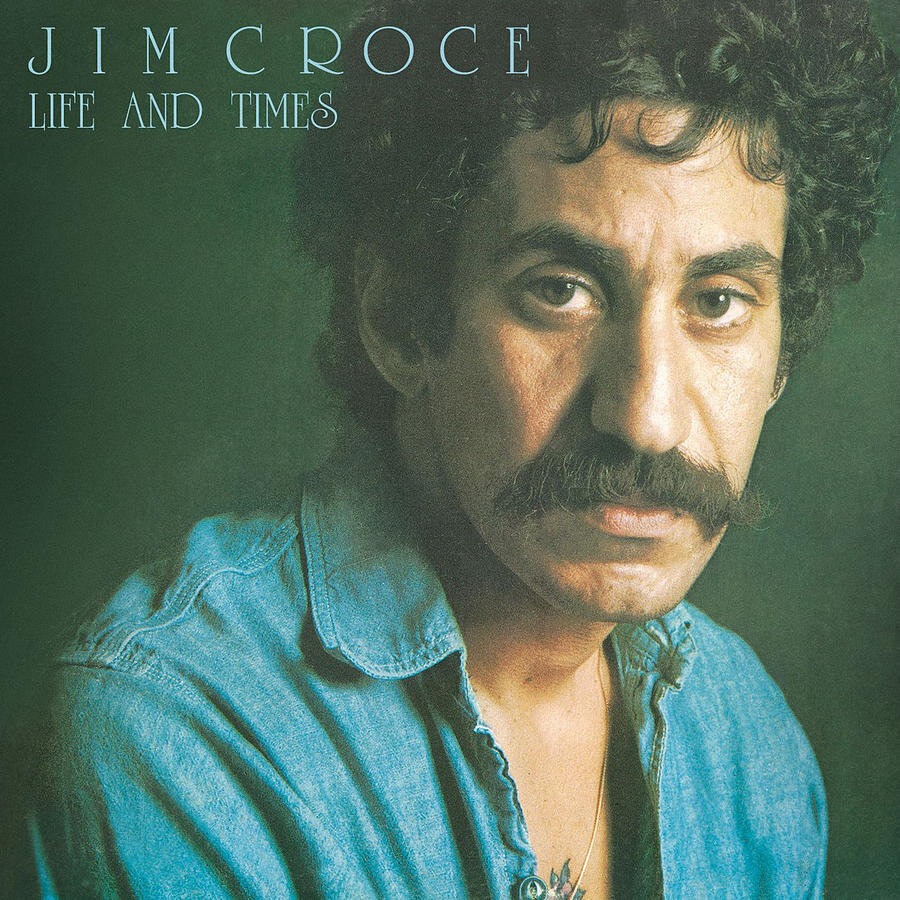

Thanks to the success of You Don’t Mess Around With Jim, Croce quickly recorded his follow-up, 1973’s Life and Times. The album birthed the #1 hit “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown,” and Croce would receive Grammy nominations for Pop Male Vocalist and Album of the Year. That same year, Croce and Muehleisen embarked on a grueling 45-date college tour of the American South. The publicity was good for the musicians, though, as Croce already had his fifth studio album, I Got a Name, in the chute and ready to be released. Unfortunately, Jim would not live to see that release.

On the night of September 20, 1973, the night before the eponymous single “I Got A Name” was released, Croce and Muehleisen boarded a Beechcraft E18S aircraft in Natchitoches, Louisiana. They intended to fly to Sherman, Texas for a show at Austin College. Tragically, during takeoff, the airplane struck a tree. The accident killed 30-year-old Croce, 24-year-old Muehleisen, and the four other occupants of the plane. Authorities determined the accident to have been caused by pilot error and low visibility caused by fog that evening.

I Got A Name would be released three months later, on December 1st, 1973. It reached #9 on the charts and produced three more of Jim Croce’s most enduring hits: “Workin’ At The Carwash Blues,” “I’ll Have To Say I Love You In A Song,” and “I Got A Name,” as well as the Muehleisen-penned “Salon and Saloon,” a piano-only ballad written as a gift to Jim. Croce’s earlier hit “Time In A Bottle” was also re-released as a single. One of the songs he’d written after finding out his wife was pregnant, the song’s poignant observations of life’s fleetingness took on new meaning with the singer’s untimely death.

Jim Croce’s death was and still is one of music’s greatest tragedies. His passing left a hole in his young family, as well as the patchwork of Americana. A week after the plane crash, Ingrid Croce received a letter from her deceased husband. In it, he alluded to wanting to leave the music industry to spend more time with her and their young son, as he felt he’d been neglecting them. He ponders the idea of getting his Master’s or writing short stories and movie scripts. Ending the letter, Croce said: “Remember, it’s the first sixty years that count and I’ve got thirty to go. I love you, Jim.”

Despite his short career, Jim Croce made an indelible impact on music. He was inducted into the Singer-Songwriter Hall of Fame in 1990. In 2022, a historical marker was placed outside of his farmhouse in Lyndell. His son, Aiden James “AJ” Croce is an accomplished musician as well, and as of 2024 is touring in the United States, playing his father’s songs on his “Croce Does Croce” tour.

50 years later, Jim Croce’s voice endures. With millions of monthly listeners on streaming services and fans new and old, the music of this Philadelphia songster has remained relevant long past his death. Because, as Jim said, “If you mean what you’re singing, people understand.”

Leave a comment